A new California Public Records Act release from last week exposes how enforcement pressure in Traci Park’s Council District 11 is actually generated and who is driving it.

The documents, produced in response to a request for communications about the oversized vehicle ordinance, show a steady drumbeat of emails from housed residents demanding the removal of people living in RVs, expanded tow-away zones, and faster crackdowns. The language is raw and often dehumanizing. RV residents are accused of dumping “shit in our sidewalks.” They are described as “entitled.” Venice is framed as “a laughing stock” because unhoused people supposedly “know rules won’t be enforced.” Others assert criminal activity as fact, claiming RVs are “selling drugs” near churches and daycares, without evidence. And some bemoan the fact that police do not have legal authority to enter occupied vehicles and remove the people inside.

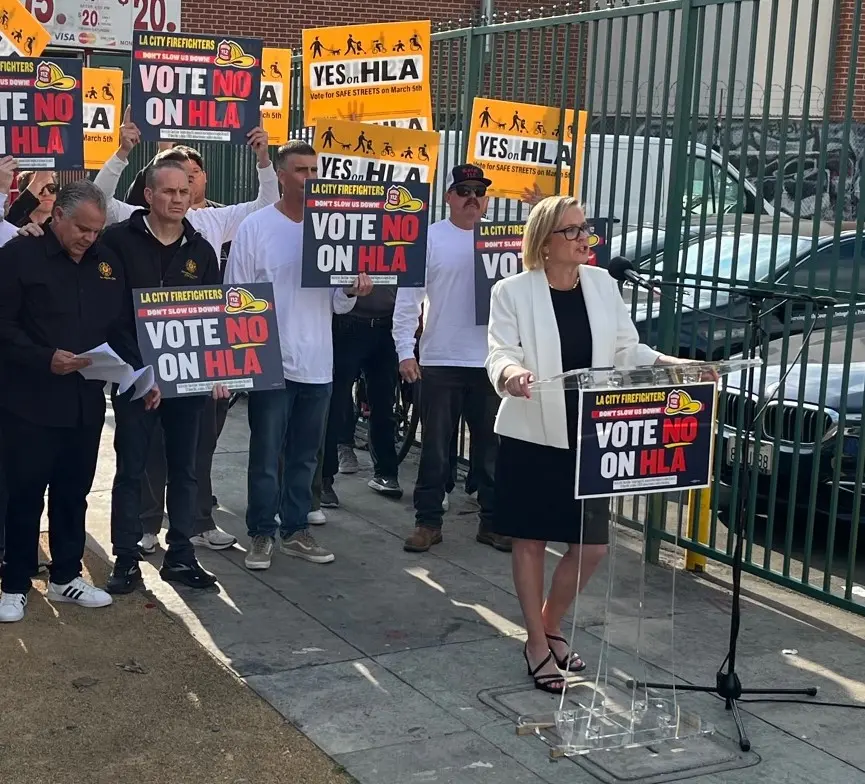

What matters just as much as the complaints is how Traci Park’s office responds. There is no pushback. No correction. No attempt to slow things down. Instead, constituents are given a how-to guide for enforcement. Staff explain petition thresholds, signage, enforcement windows and what legislation is coming next. This is not constituent service. It is policy assembly.

Complaints become petitions, petitions become motions and motions become new tow-away zones, over and over again.

The CPRA shows Park repeatedly assuring residents that stronger enforcement tools are coming. She commits to continuing the block-by-block expansion of oversized vehicle restrictions under LAMC 80.69.4 and signals that current limits are temporary.

In public, Park has pointed to Assembly Bill 630 as the solution, framing it as the mechanism that would finally allow Los Angeles to seize and destroy RV homes outright. Earlier this month, a judge ordered the city to halt the rollout of AB 630, finding that Los Angeles does not have the legal authority to use the law in the way Park described. The enforcement power she promised does not legally exist.

None of that stops the assurances. In the CPRA record, Park’s office continues to speak to constituents as if expanded enforcement is inevitable.

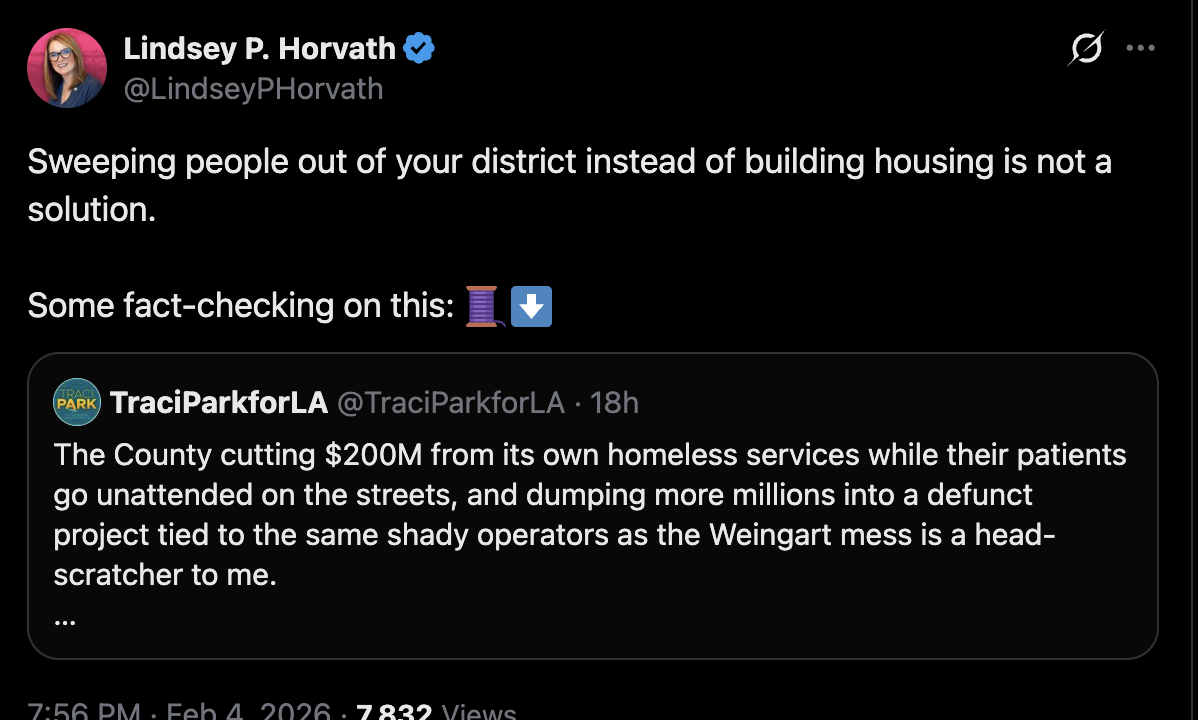

Equally telling is who does not get a response. Emails from mutual aid volunteers and community advocates asking for coordination or restraint largely go unanswered. In one message, a volunteer asks the office to pause enforcement so outreach groups can connect with people living in RVs, warning that “moving people right now will just scatter them before we can help.” The email is forwarded internally. Then it disappears.

That contrast is the story. Residents calling unhoused people filthy, criminal, and disposable receive prompt replies and legislative follow-through. People asking for care or coordination get silence.